The history of America’s fraternal orders is in part the history of a variety of non-denominational quasi-religious sub-groups, groups in which members found a purpose and meaning in life through service to others. But some fraternal orders served other less noble purposes as well. Some orders resembled a college fraternity as much as a benevolent service organization. One of the features of such fraternal orders, like college fraternities, was the opportunity for male bonding. A college fraternity helped its members bond together in making the transition from adolescence to adulthood. A fraternal order helped socially insecure but ambitious male members rise in the world. Fraternal orders were better suited to go-getters than to those who had already gotten. Some orders, particularly those formed in the Midwest, were bastions of middle class conservatism, but not everyone, not even in the Midwest, approved of middle class conservatism. H. L. Mencken, by combining the words bourgeoisie and boob coined the term booboisie for the American middle class, whose stronghold historically has been the Midwest. Sinclair Lewis’s novel Babbitt (1922) added a new word to the American language, babbitry, which meant a smug and materialistic way of life hypocritically cloaking itself in civic boosterism and piety. Lewis’s character George Babbitt lived in the fictional Midwestern city of Zenith, which was thought to be modeled on Cincinnati, where Lewis lived while writing the novel.

By 1900 there were over a thousand fraternal orders in the United States, six hundred of which were secret societies emulating the fraternal order of Masons, which over the centuries had become the most important and influential fraternal organization not only in America but in the world. The Masons had already established the “builder” brand, identifying themselves with the masons who had built the pyramids of Egypt and cathedrals of Europe in the Middle Ages. But Masons claimed to be descended not just from the builders of pyramids and cathedrals but to be descended from the builders of human society, the architects of civilization itself. Without the Masons, whose membership included everyone from George Washington to Ben Franklin and Paul Revere, there probably would not have been an American Revolution, or at least not a United States of America, at least not in 1776. But the Mason’s notorious secrecy, hierarchic structure, and ritualistic rigmarole had turned off many Americans as being undemocratic and un-American. After the Revolution, Masons were suspected of all kinds of skulduggery, including the assassination of members who violated the solemn Masonic oath of secrecy. The fraternal orders that followed in Masonic footsteps by adopting the builder brand were adopting a brand that had become, in the eyes of many Americans, very tarnished. By 1900 there was a need of and a niche for a fraternal organization that would create a new more distinctly American brand, in which backslapping would replace secret handshakes. The way in which Kiwanis emerged as that new brand is an example of how big organizations, like mighty trees, can grow from little nuts.

In a Hole from the Start

In 1915, what would later be called the Kiwanis Club of Detroit Number One, was founded by Joseph C. Prance, a tailor, and Allen S. Browne, a salesman type, who had made a career of starting fraternal organizations, which gives us an idea of how many organizations there were when somebody could make a career of organizing them. Browne and Prance found themselves in a hole right from the start. For example, they named their new fraternal organization the Supreme Lodge of the Benevolent Order Brothers, or B.O.B., for short, not exactly a catchy moniker. In calling what they created a lodge, rather than a club, they were being too Masonic and not clearly American enough. It may have been Browne, since he would have had more marketing sense than his tailor partner, who realized their mistake and came up with a more American name for B.O.B. What could be more American than an Indian name? Look at how many states have Indian names, such as Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, and Ohio? Why shouldn't a fraternal order have an Indian name? Browne and Prance chose a new name based on an Indian expression, "NunKey-wan-is." But, oops, they found themselves in another hole. "NunKey-wan-is" meant, “We have a good time—we make noise,” which might be a fitting name for a fraternity but not for a fraternal order that wants to be taken seriously as a benevolent society. (I got these details from an official source: “Kiwanis: Past to Present,” a brief history.) So the Kiwanis Club of Detroit Number One, as it became known, had to make another change. But having changed its name once already, taking a third name would only make establishing a new brand that much more difficult. Instead of changing the name Kiwanis, they changed the meaning of the phrase "NunKey-wan-is." After all, other than native Americans, of whom we can be fairly sure there were few or none in Kiwanis, who was going to know what the meaning of "NunKey-wan-is" was anyway? The important thing was Kiwanis became an organization that enabled bonded brothers to join together in serving humanity and to scratching each other’s back in business. Some form of insurance came with membership, so the commercial dimension was present in Kiwanis from the start.

So to attain respectability and escape the stigma of having begun an organization that sounded like a bunch of frat brothers, they assigned a new meaning to Kiwanis to suggest something more appropriate to the serious brand they were trying to establish. Instead of changing the word, they changed the word’s meaning. The notion took hold among Kiwanians that "NunKey-wan-is" meant not “We have a good time—we make noise,” but rather “we make and build.” In 1920, the editor of the Kiwanis magazine capped this trend by creating a simple civic-minded slogan: “We Build.” But in rebranding their organization by changing the meaning of "NunKey-wan-is" the Kiwanians got out of one hole only to find themselves in another. The problem with the “We Build” slogan was that it not only sounded Masonic, it sounded a bit moronic. In rebranding themselves as builders, they had reverted to the Masonic brand, and from a marketing perspective that was not the best move. But that was not a problem that Browne and Prance were destined to solve, because the Kiwanis Club of Detroit Number One fell apart after Browne was accused of putting the club in the hole financially by pocketing membership dues. But other Kiwanis clubs were founded in Chicago and Cleveland, and the movement that had begun inauspiciously and somewhat shadily in Detroit grew into a national and international organization, in spite of the marketing mistakes of Browne and Prance. But Kiwanis would remain fundamentally Midwestern in character and spirit, and it was appropriate that its headquarters would end up in Indianapolis in the quintessentially Midwestern state of Indiana. An argument could be made that the quintessential Midwestern state is Ohio and the appropriate site for Kiwanis headquarters would be Cincinnati, where George Babbitt was conceived.

To get out of the marketing hole of the “building” brand, Kiwanis went on to rebrand itself in a way that transformed the field of fraternal orders. It rebranded itself as the fraternal order that cares, and cares above all about children. With caring for kids as their new mantra, Kiwanis struck marketing gold, and ever since, in a kind of endless summer, has been surfing on that marketing wave. And why wouldn’t it? Is there any human emotion more universal and deeper than love of children? Not just parents, but adults in general love children. In children adults can simultaneously glimpse the future and take a trip back to their own past. How could an organization that adopted as its mission the welfare of children not succeed and become a powerful and influential international organization?

Snookered City

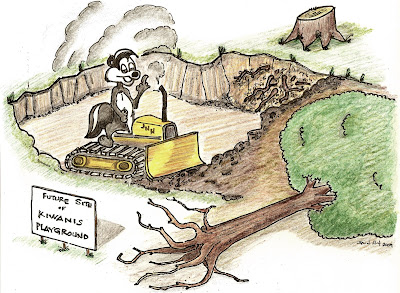

But the Kiwanis "kid caring" brand still retained some of the Masonic “builder” brand. “Caring for Kids” became the successful brand and the “building” shtick was subordinated to it. Middle school students can now join Kiwanis “Builders Clubs,” but in terms of marketing, the “builder” brand is about at the middle school level. Kiwanians are still in the building business but only in so far as they build for kids. They build everything from hospital wings to playgrounds for kids. Ka-Boom! and its “Playful” brand, which I have written about before, has managed to horn in on the playground business, and naïve public officials all across America have been snookered into proudly posting signs that proclaim theirs as a “Playful City,” even though in many cases those cities were losers in the Ka-Boom! competition. A sure-fire contest is one in which everybody is a winner, even the losers. Compared to the Kiwanis brand signs at the entrance of many cities, the “Playful City” brand provides about as much brand recognition as British Knights in the sneaker world have vis-à-vis Nikes. It is ironic, in view of the tree and kid issues involved in the current Kiwanis Playground mess in Portsmouth, that on the way into town on Route 23, drivers pass an “Arbor City” brand sign under a “Playful City” brand sign. The sign that drivers should see as they drive into Mayor Kalb’s hometown is “Portsmouth: the Snookered City.” Or, better yet, Portsmouth should be called not "Tree City," but "Paw City," for reasons I gave two postings ago.

Welcome to Snookered City

The controversy over the Kiwanis Playground illustrates the holes Kiwanians are still capable of digging for themselves. The spirit of Prance and Browne lives on. Kiwanis is such a powerful and influential organization that when it finds itself in a community, such as Portsmouth, where local government has atrophied and where the incompetent and the unindicted too often end up in public office, then it is hard for the high-minded mission-oriented Kiwanians not to become arrogant and to overreach, as they apparently have in regard to the Portsmouth Kiwanis playground.

Gathering Round the Hole

I spent an hour or so Friday morning (18 Sept. 2009), one of about twenty-five people who had gathered around a gaping hole in Tracy Park where the playground was supposed to be built. Standing around the hole, we were able to listen to and ask questions of the state forest ranger Ann Bonner about the Tracy Park Kiwanis playground mess. Construction of the playground had been halted the previous week after concerns had been raised about the safety of the trees and more importantly about the safety of the children who would be using the playground. What struck me most about the round-the-hole discussion was why the number of important issues and problems that were being discussed—largely related to environmental and engineering issues— had apparently not even been raised before. What I came away from that discussion with was the sense that the Kiwanis and Mayor Kalb had dug themselves into a public relations crater that was much deeper than the hole we had stood around. That physical hole will soon be filled in and the playground built, but the Portsmouth Kiwanis Club is going to be in a public relations crater for a long time.

Initially, on the basis of what he could see, a Portsmouth horticulturalist, Ray Gibson, didn’t think any tree roots had been destroyed. But James Warnock later said he had witnessed large roots being bulldozed and hauled away. Warnock also said that employees and equipment belonging to Neal Hatcher’s construction company, JNH, had helped the city in bulldozing and trucking the roots away. (Somebody told me Hatcher had denied to the Portsmouth Daily Times that his company was involved in any way.) If large roots had been removed, then the trees might be damaged. But it usually takes trees four or five years to show signs of root damage. Gibson proved to be so knowledgeable about how the playground project should have been built that Rick Morgan, representing Kiwanis, asked him if he would be willing to serve as a consultant on the project. Again I wondered why Kiwanis had not got Gibson or some other horticulturalist on board, and contacted a state forest ranger, in the beginning. It seemed to me like the barn door was being closed after the horse had bolted. Do you get a horticulturalist involved only after tree roots have been ripped out?

The question I asked at the round-the-hole discussion was whether the Portsmouth Kiwanis Club and the city had a written agreement. Rick Morgan, speaking for Kiwanis, replied there was. That written agreement could be a very important document in helping resolve this controversy. Mayor Kalb should make that agreement public. The Portsmouth Daily Times reported that when they finally reached Kalb in North Carolina last weekend, he said “that the first time he heard there were any problems with the project was Thursday [10 September 2009] when he began receiving calls from concerned citizens that digging may be damaging important trees and state-listed trees.” The PDT then quoted Kalb as saying, “For some reason, when they started digging, they moved from the original location and now the playground is around some trees” (emphasis added).

If there is a written agreement, and if Kiwanians changed the agreed upon site in the written agreement, that raises ethical and legal issues. Who do they think they are, changing the location of the site without the city government or even the mayor knowing or approving of the change? By changing the site, the Portsmouth Kiwanis Club may possibly be jeopardizing not only the well-being of the trees but more importantly the well being of the children, the caring of which is supposed to be the essence of the Kiwanis brand. The hazards associated with having the playground on the busy southeast corner of Tracy Park is the reason some people are objecting to the playground. Some residents feel that, ideally, the playground should not be located anywhere in Tracy Park, because the park is like an island surrounded by a heavy flow of traffic. It was certainly surrounded by a loud sometimes fast stream of traffic on Friday morning, when the round-the-hole discussion took place. One passing motorist rolled down his window and angrily shouted something like, "That's no place for a playground!"

Keep Your Eye on the Holy

“The Six Permanent Objects of International Kiwanis," underscore the spiritual and humanitarian goals of the organization. But let us be intellectually honest and recognize those goals as religious, even if the organization itself denies it is a religion. Keep your eye upon the holy and not upon the hole. The Six Objects are the Six Commandments of Kiwanism, and one of those “Objects” is revealing and deserves close scrutiny: “To develop, by precept and example, a more intelligent, aggressive, and serviceable citizenship.” “Aggressive” is the revealing adjective in that Kiwanian Object, because aggressive is just what Portsmouth Kiwanis has been from the start in the marketing of the Kiwanis playground project. The two Abrahamic faiths that grew out of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, became progressively more aggressive in marketing their brand until now it seems the rivalry and hatred that exists among the three Abrahamic faiths may result in the nuclear annihilation of civilization. Some “builders” they turned out to be! Masonry was as successful as it was in part because it denied it was a religion at the same time that it secretly acted like one. The Catholic Church knew a rival when it saw one and excommunicated Catholics who joined the Masons. The Kiwanis took after the Masons in acting like a religion, and a very aggressive religion, while denying it is one.

In this Kiwanis Playground controversy, anger and hatred are being stirred up against those who have concerns about the project. James Warnock and his wife Donna are among those who are being demonized because they have expressed safety concerns about the project. They are being accused by politicians of being political. The safety concerns are being dismissed as “political.” The Warnocks are not politicians. They are citizens who happen to have reservations about locating the Kiwanis playground in Tracy Park. The only organization they have been involved with is the Portsmouth Beautification Society. Donna Warnock resigned from the society recently, claiming it had originally been opposed to putting the playground in Tracy Park, but because of political pressure the society had become a backer of the playground in the park. For not agreeing with Kiwanis and the Beautification Society that Tracy Park is the best place for the playground, the Warnocks, a low-key couple, are being characterized as meddlers and trouble makers.

The Portsmouth Kiwanis Club has to understand that they have no monopoly on caring about kids. Their brand may be caring for children, but in this playground mess I think they are showing a callous disregard for children. They may be guilty of wanting to publicize the good they are doing for children so much that they are willing to put the Kiwanis playground on the most dangerous corner in Portsmouth. They may be following that real estate adage—location, location, location. As a result of the aggressive marketing of their brand, the people in the hundreds of thousands of vehicles that will drive by that corner annually will be reminded of what a wonderfully kid-caring organization Kiwanis is, but they better keep their eyes peeled for kids unaccompanied by adults dashing across Rte. 23 to get to the playground.

There has been an attempt by Kiwanis, the mayor, and the media to shift the focus from traffic and kids to trees and roots, and to portray James Warnock as a tree-hugger. But Warnock made clear to the PDT, “My main concern is and always has been, first and foremost the placing of a children’s playground in a busy commercial area and secondarily, the health of the historical trees in Tracy Park.” This is not just about trees and roots; it is about children and traffic. But the party line the PDT is peddling is that it is about trees and roots, as is evident in John Stegman's "Stopping the March of Progress" and Frank Lewis's "Let's Move Forward with the New Playground." I am surprised Lewis could not come up with a quote from Abraham Lincoln in favor of Kiwanis playgrounds.

The cause of the Playground controversy is not the Warnocks, it is Kiwanis and Jim Kalb, our Out-to-Lunch-and Off-to-Another-Motorcycle-Race-in-the-Carolinas-Mayor. I think the image or “brand” Kalb has created as mayor is, “I’ll let you do what you want if you just let me take long lunches and long weekends in the Carolinas living out my Marlon Brando Wild One fantasies.” If the mayor had been minding the store more, if he had been monitoring the playground project better, this controversy might have been avoided. Being out to lunch is one thing, but being in North Carolina and not knowing that Kiwanis had shifted the site of the playground is another.

Unwise and Unlawful

As things now stand, the playground may be not only unwise but unlawful. It may be in violation of Ohio Revised Code 713-02, dealing with a local planning commission’s duties and powers. ORC 713-02 states that nothing, including a playground “shall be constructed or authorized to be constructed in the municipal corporation, or planned portion thereof unless the location, character, and extent thereof is approved by the [planning] commission.” I am not aware that the planning commission, the city council, or any other body has considered and approved the Kiwanis plans for the playground.

Kalb’s motorcycle fantasies, or chickens, may be coming home to roost in the Kiwanis playground mess, and those chickens could morph into vultures, since the lives of the trees and the kids crossing the heavy traffic to get to the playground may be at stake. That may be the truth, the unholy truth, about the Kiwanis playground controversy.

For an important follow-up on this post be sure to read, "Kiwanis Playground: Deathtrap for Tots" (click here).